Hani Abbas is lucky. In a hotel lobby in Lausanne, Switzerland, the internationally recognised Syrian-Palestinian cartoonist cuts a humble figure in a black blazer and scarf. Fair-skinned, with dark green eyes, he looks like someone only just coming to accept his current circumstances.

“I never intended to leave Syria, not even Yarmouk,” he says, shrugging. “I was against leaving. It just happened.” He and I communicate in Arabic, often across one – sometimes two – translators. At one point, I try to ask a question but the word “process” proves untranslatable. Abbas laughs about his tentative French. “When my wife arrived with our son, she asked me to teach her ten words of French a day. So I taught her ten words, and then I told her ‘School is closed, that is all I know.’”

As part of his settlement process, the Swiss Government put Abbas through a three month French course, but he wasn’t able to focus on learning the language while so much of his life was uncertain. Now, with his residency firmly approved and his wife and son permitted to join him in Switzerland, he plans to start language courses.

Abbas lights up when he tells the story of how he met his wife. They met at an art exhibition and wrote each other letters. She was from Hasaka, a long way from Yarmouk, and it took five years for her father to agree to their marriage. Abbas took fifteen sheikhs to her village in Hasaka to witness the agreement between him and her father. His future wife’s father imposed two conditions: that Abbas buy a house, and serve in his mandatory two years in the Syrian army. Even though Syrian-Palestinians are not granted full citizenship, they are still obligated to serve in the army. All told, Abbas waited seven and a half years to marry his wife.

Those seven and a half years were much longer than the year or so Abbas waited for his Swiss residency. He repeats insistently that he never intended to leave Syria. His loyalty is something I can’t understand, coming as it does from a man persecuted and arrested by his own government for speaking out.

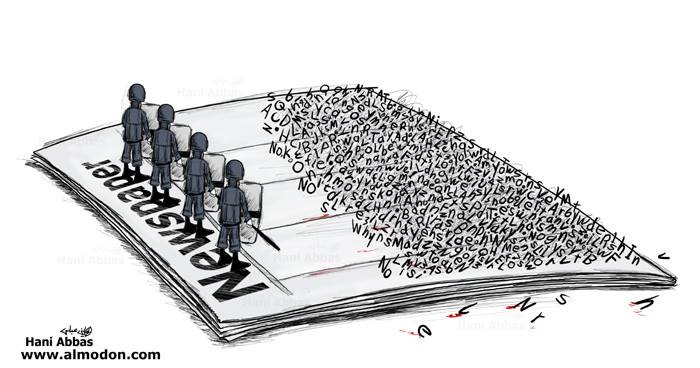

At the beginning of the Syrian revolution, the secret police took a particular dislike to Abbas after he published cartoons about army defectors. While his colleagues were disappearing, tortured, and killed, Abbas moved around the country, to Derraa and back to Yarmouk, looking for a safer environment. Eventually the situation forced him to escape to Lebanon.

Abbas found work, sending cartoons to Al Jazeera, Al Hayat, and Al Nahar, but life was not easier. “Even in Lebanon, the situation is unbelievably bad,” he says. In a small country whose diverse population of 4 million is increased daily with refugees from Iraq and Syria, tensions are mounting. His work continued to draw criticism and threats, endangering Abbas and his family.

Just as his situation was becoming untenable, Abbas was saved by an angel named Roberta who found him on Facebook. She wanted to put on an exhibition of his cartoons in Geneva and arranged for him to travel to the opening in Switzerland. “They talked me into it,” he says, smiling. The opportunity to leave couldn’t have come at a better time, yet despite the danger of continuing to work in Lebanon, Abbas had no plans to stay in Switzerland. “It would have been bad manners to go for an exhibition with official permission and stay. I thought maybe I would go to Germany or Sweden, but not stay in Switzerland.”

But Roberta persuaded him to meet with a lawyer and he applied for residency. The Swiss authorities in Geneva kept him in a refugee centre for twenty days before moving him to a shared home in another canton. He spent six months in a house with five other men, all of them Afghanis. “I felt I was living in Afghanistan, not in Switzerland. The food, the language, the way of living, it was all Afghani.” He then spent another six months with five Eritreans. Many of them had never seen a Western toilet before, let alone mobile phones, tvs, and kitchen appliances. “They used to call each other on their phones from different rooms,” he says, shaking his head.

His refugee story took an even more unusual turn when he was presented with the “Press Cartoonist Award” by Kofi Annan. Shortly after, the Swiss authorities granted him residency, along with his wife and son. “I expected their residency process to take six months, maybe a year, but it happened in a week.”

Abbas continues to contribute cartoons to Al Modon and Al Jazeera. He is constantly inspired, and carries looseleaf printer paper in his bag, sheaves and sheaves of scribbles. “I show my wife and ask her what she thinks of the drawing, and she says “what? what drawing?” He passes me sheets of paper and I admit that it’s hard to make out the final product on the page of small ideas, false starts, and hurried notes in sprawling Arabic script. The commissions he earns from these papers used to last one month in Syria or Lebanon. Now he finds that they are not enough to cover a week in Switzerland.

But he is very thankful. “Roberta has been like an angel, it isn’t normal,” he shakes his head, smiling. “She is always checking on me, my friends say she’s like my mother. Every magazine I could work for she goes to talk to, every step of the refugee process she is there, every meal she asks if I’ve eaten.”

The next step, he says, is to try and get his parents out of Yarmouk. “This will be very difficult,” he says gravely, “because no country wants to take old people.” He has a brother in Sweden and another brother who moved to Spain before the war. His sister is a doctor in Saudi Arabia. His family, like so many other Syrian-Palestinian families, is in the second phase of the Diaspora.

Like so many Syrians, Abbas has become comfortable talking about home in the past tense. He describes Yarmouk eagerly, explaining that although it is known as a Palestinian refugee camp, it is actually home to more Syrians than Palestinians. Or it used to be. Yarmouk was a centre of commerce. Banks, shops, and every business you can imagine were all crammed into the mini-city. In Arabic, it’s called “The Tents Of Yarmouk”, as a way to make people understand that it’s a refugee city. But there are no more tents. The concrete clusters of buildings piled one on top of the other are now permanent.

This reminds Abbas of another story of the chronic fear of the refugee, the fear of staying in the wrong place. “My friend, he is an Iraqi-Palestinian. In 2003, he left Iraq with some other families and they made it to the desert near Hasaka on the Syrian-Iraqi border. They stayed there for some years and he refused to put down a single stone. He knew as soon as he did that he would stay. In the end, he walked to Turkey and tried to get out from there. Only in this last few months, he made it to Canada.” When a refugee leaves, they take hundreds of these stories with them, the warnings of generations who thought they would eventually go home.

Getting out of Syria is particularly difficult for Syrian-Palestinians. Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan have refused them entry because their papers are considered unofficial. Before the war, Syrian-Palestinians had “temporary residence” status in Syria. Though their ID cards had no national ID number, they were considered sufficient for travel. Now, neighbouring countries already swollen with refugees are using any excuse to bar entry to those fleeing the conflict. Syrian-Palestinians, technically stateless, are frequently deported back to Syria.

In the face of ISIS, Ebola, and other major international news, the day-to-day life of Syrians is largely under-reported. And yet their stories are nothing short of harrowing. “Any Syrian, even if they live a simple life, their last four years is like a novel,” Abbas says. The conditions people have come to regard as normal should only be understood as extraordinary. Food and medicine are in low supply, and extremely expensive when found. “Lettuce in Syria used to cost 10 LY before the war. Now it costs 300 LY in government controlled areas if you can find it.”

Abbas understands that though Syria appears occasionally in the Western headlines, there is no appetite for the country’s suffering. “Hillary Clinton spoke out about that detainee, and there was that British doctor a few months ago. But the Syrian government is left alone in its own bubble and no one picks up the phone anymore to hold it accountable.”

With the number of actors on the scene and the volatility of the situation on the ground, Abbas is unsure of what’s next. “You used to be able to predict what the situation was going to be – not anymore.” You can be sure that whatever happens, Abbas will help to make sense of it with his dark, funny and insightful cartoons.

All photos courtesy of the artist’s Facebook page